A Particular Review of the History of Writing Through an AI Prism: Saliency and Prevalence in Derived Scripts

Disclaimer: this is a daring experiment made of history, arts, and computer vision technology. Any possible misattribution or inappropriate lack of scientific rigor should be immediately quarantined to be saved from rational arguments.

Warning: the following text contains a high dose of Wikipedia hyperlinks. Exercise the utmost restraint in its consumption.

“Writing is one of the most important inventions ever made by humans. By putting spoken language into visible, material form, people could for the first time store information and transmit it across time and across space. It meant that a person’s words could be recorded and read by others — decades, or even centuries later. It meant that people could send letters, instructions, or treaties to other people thousands of kilometers away. Writing was the world’s first true information technology, and it was revolutionary. The very ubiquity of writing in our civilization has made it seem like a natural, unquestioned part of our cultural landscape. Yet it was not always this way. Although anatomically modern humans have existed for about one hundred thousand years, writing is a relatively recent invention — just over five thousand years old. How and why did writing first appear?”

— Gil J. Stein in Visible Language, inventions of writing in the ancient middle east and beyond. The University of Chicago, 2015.

The quote above beautifully depicts the significance of writing. Personally, the research on the appearance of writing and how some writing systems evolved and diversified in other alphabets is simply fascinating. Reasons for its evolution could be the transference of symbols between civilizations by cultural influence, trading and accountability registers, or script adaptation to the recording medium. Some cases are well documented, or at least deducible from small inscribed tokens or double messages innocently left in a stone statuette. However, other mysteries of the history of writing still remain secret, waiting to be discovered.

In the evolution of writing systems over centuries few characters remained intact for a long time. While many mutated in shape, others simply didn’t prevailed. In terms of visual perception, a possible question is to what extent some visual features are shared between derived scripts. For instance, how much is preserved by the Latin alphabet from any of its scripting ancestors? Or —in a triple somersault with six pirouettes— Do any special geometry or hidden layouts exist which induce certain sign marks to be recognized as scripting?

A particular adventure is proposed here. It consists in exploring and tracing back remaining visual features, if any, between the Latin script, its historical ancestors, and all the way back to the origin, the Egyptian hieroglyphs. That far? Sure! an incredible long way back.

After me explorers!

A note on text detection with convolutional networks

Artificial Neural Networks, as part of the Artificial Intelligence (AI) field, have become probably the most exciting mathematical construction in the last decade. Although firstly proposed by W. McCulloch and W. Pitts in the 40s, and later expanded at the turn of this century by scientists like Y. LeCun, Y. Bengio & G. Hinton, their widespread use did not explode until an increasing computing performance, huge storage capacity and tremendous data availability took place. Computer Vision —or how to make computers see— has radically benefited from it to accomplish unbelievable tasks just a few years ago.

In particular, Fully Convolutional Networks (FCN) perform image analysis with millions of local operators —or convolutional filters— stacked on a series of increasingly narrower and deeper interconnected layers, resulting in highly abstract visual features. After a sophisticated training procedure with millions of images, such deep networks learn abstract patterns on images associated with complex objects, for instance the category cat in any of its multiple representations.

Throughout this article, I used this TextFCN trained exclusively with Latin characters from the COCO-Text dataset with hundreds of thousands of text instances and multiple fonts. It is important to understand that every alphabet by itself may give rise also to multiple typography anatomies —usually in connection with a particular purpose. The detection of highly variable Latin characters and words previously shown by the TextFCN gives an idea of the generalization and therefore abstraction capacity showed off by deep neural networks in recognizing things “unseen” before.

Classical antiquity: the Roman and Hellenic forefathers

The Roman Empire was one of the greatest empires of all times, which ruled with firm hand about 5 centuries (27 BC-476 AD) in a vast amount of territories around the Mediterranean Sea and more distant lands, such as the whole Iberian Peninsula (Hispania), Britannia, or the Euphrates valley in Mesopotamia. The Roman regime would sadly conduct some of the most darkest moments in history, but its domination was also made possible by means of important contributions on architecture, administration, law, language, or arts, which would had a profound influence on posterior civilizations until present days. A clear example was the propagation of the Latin Alphabet, which would become the world’s dominant writing system.

The large latin inscription of the iconic Pantheon of Agripa —constructed between 27 BC–14 AD in Rome— reads “M[arcus] · AGRIPPA · L[ucii] · F[ilius] · CO[n]S[ul] · TERTIUM · FECIT”, meaning “Marcus Agrippa, son of Lucius, made [this building] when consul for the third time”. However, the current temple was built decades later, around 126 AD by order of Hadrian. The rear part of the original peripteros temple was demolished and in its place a cylindrical building was erected behind the portico and culminated in an exceptional dome. As few buildings after the collapse of the Roman Empire, it rarely survived due to its continuous use as a Christian church.

Western thought has firmly assumed in many aspects that Classical Greece is the cradle of its civilization. Certainly, the influence of Greek culture, by means of remarkable philosophies, mathematicians, sculptors, architects, and writers, left a significant mark in Western culture. However, popular lore ignores, and some academics absently look the other way on recognizing Western roots beyond the European boundaries, to the Near Middle East or even Northern Africa. For instance, a large Greek community in Egypt used to travel and stay in the land of pharaohs, some to learn mathematics, architecture or medicine. This could explain that many of the Egyptian literature curiously recalls some of the great antic Greek narratives and myths, and not to mention the strong resemblance between their deities and festivities.

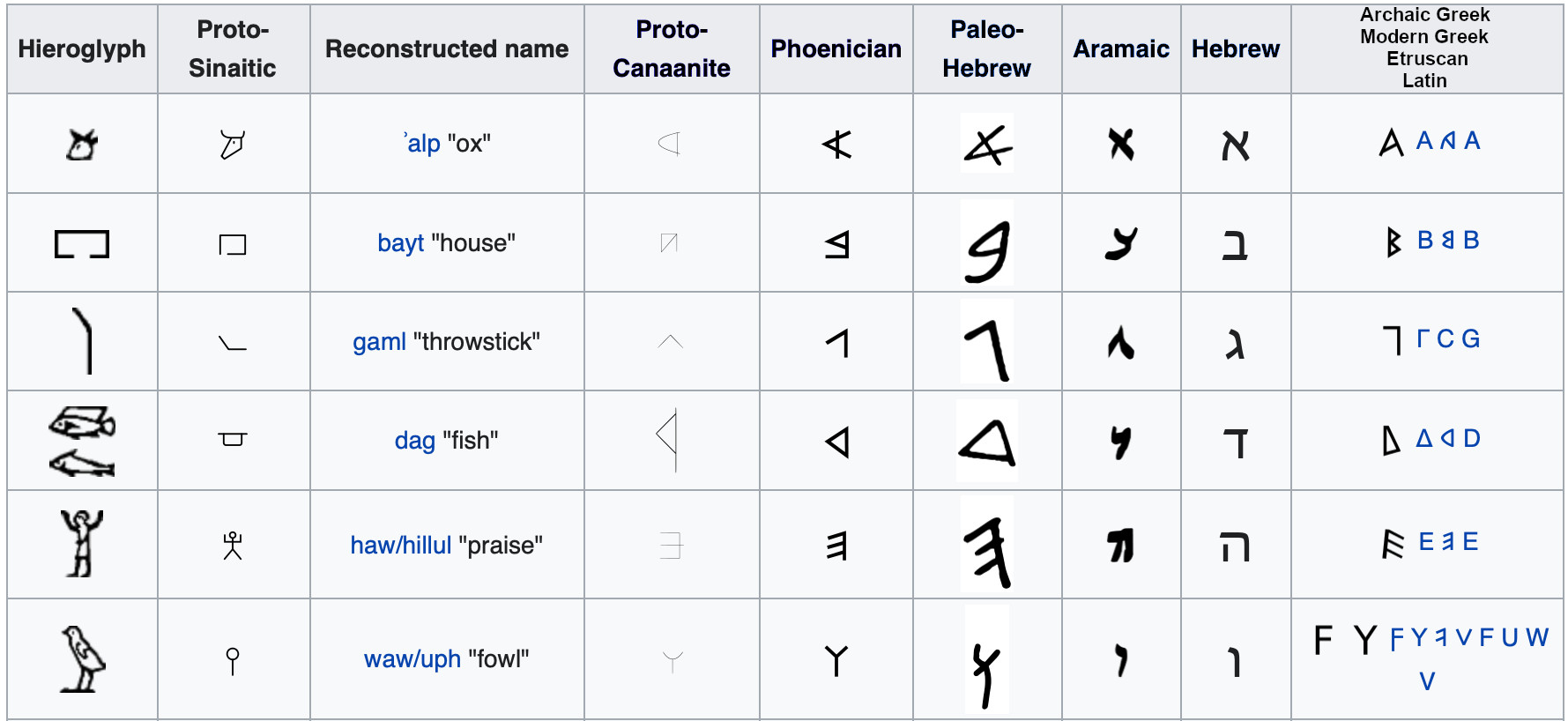

Regarding the Greek Alphabet, most of its characters were borrowed from the Phoenicians, as many other contemporary alphabets in fact did. Besides the palpable evolution of shapes, one of the most important difference —and a historical milestone— is that the former adapted some letters to represent vowels, non-present in the latter or previous alphabets. Furthermore, the Greek alphabet gave rise to numerous derived scripts, not only Latin, but also Cyrillic, Runic, and Coptic.

Phoenician: one alphabet to inspire them all

With the decline of most great empires at the Late Bronze Age, the Phoenician civilization emerged in the Levant region predominantly between 1500-300 BC. They became sailors in the first place and rapidly expanded across the Mediterranean influence area, going down in history as audacious explorers and clever merchants. Precisely, their extensive trading activities stimulated the exchange of knowledge between prominent and influential civilizations such as Greece, Egypt, and Mesopotamia. Among all exchange items, the Phoenician Alphabet was of paramount importance. The development of shapes of the Phoenician letters over the course of the 1st millennium resulted in diverse alphabets such as Aramaic and Archaic Greek, which over centuries diversified into contemporary widespread alphabets such as Hebrew, Arabic, Cyrillic or Latin. The Phoenician alphabet apparently provided stabilization in terms of direction and orientation of the letters and the direction of writing (right to left).

Proto-Canaanite: the missing link

The profuse and dilated history of the Ancient Egypt —nearly across 3 millennials, easy to say— cannot be conceived without its intimate and mostly turbulent relationship with its neighboring kingdoms. The Egyptian eastern frontier fluctuated over the centuries, between what now is Gaza and the present Syria. It was caused by recurrent military conflicts with the Asiatics —as Egyptians used to call any civilization coming from the east— such as the great Assyrian Empire or the mighty Hittite Empire. Not without reason, the Nile Delta, with its open marshlands rich in fish, fowl and fertile crops, was an attractive territory to conquer or defend.

Among all conflicts, the Battle of Qadesh between the forces of the renowned and long-lived Ramesses II and his counterpart the Hittite king Muwatalli II about 1274 BC, has gone down in the annals of ancient history in the form of numerous texts and wall reliefs. That confrontation eventually would lead in 1269 BC to the earliest known parity peace-treaty between two great powers.

In this border area, Canaan —an umbrella-term used to refer a semitic civilization and region along the Near East Mediterranean coast— acquired particular importance during the Late Bronze Age with the “damnated” Amarna period (14th-century BC). An evidence of prolonged boiling activities in this region is the King’s Highway, an ancient trade route sprinkled with a series of fortified structures whose old remains last until today.

In this active context, a modest reddish sandstone sphinx —dated 1800 BC (c.) and discovered by Sir W. M. Flinders Petrie around 1904 in the ruins of a Temple of Hathor at Serabit el-Khadim, an antic turquoise mining area in the southwest Sinai Peninsula— is sometimes considered the Rosetta Stone of the Proto-Sinaitic script. It turns out that the same message was carved on the sphinx in both languages. Thus, the right shoulder hieroglyphs read “Beloved of Hathor [mistress] of turquoise” and the left base —deciphered by Sir Alan Gardiner in 1916— reads “to [the] Lady”, that is Hathor. The Proto-Sinaitic symbols were invented —as hypothesized by John and Deborah Darnell in 1999— by Egyptian scribes to allow them to communicate with Asiatics, especially during trade transactions. The resultant consonantal alphabet, which adapted the hieroglyphic script but Phoenician phonetics, observed over the years a gradual evolution away from purely pictographic shapes to more abstract and stylized forms. It was later adopted by the Canaaneans and hence renamed Proto-Canaanite.

This sphinx presumably provides the missing link between the hieroglyphic or hieratic signs and the Canaanite writing, which would be adopted by the Phoenicians several centuries later.

Ancient Egypt: the origin of many

The transformation of the Ancient Egypt during nearly 3 millennia (3150-332 BC) walked over three splendor kingdoms and three intermediate periods of instability, coming to an end after the reformed and turbulent Ptolemaic Kingdom (332-30 BC). Few empires were able to vigorously reborn so many times from severe crisis though. The Old Kingdom is also known as the “Age of the Pyramids” —never again constructed of that size or at least so resilient to remain upright until the present time— when fundamental cultural and religious conceptions were established and accompanied the empire all along its lifespan. The Middle Kingdom is considered ancient Egypt’s Classical Age during which some of its greatest works of art and literature were produced, such as The Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor or The Story of Sinuhe. The New Kingdom was reigned by renowned kings such as the Thutmosesi, the Ramessesi, the Amenhoteps, Tutankhamun and the brave queens Hatshepsut and Nefertiti, most of them buried in the fascinating tombs of the so-called Valley of the Kings.

To reconstruct the history of the Egyptian Dynasties, the Aegyptiaca of Manetho was a key document. In it, the Ptolemaic priest enumerates an exhaustive king-list from the Old to the New Kingdoms. Apart from it, some important artifacts from different Kingdoms have survived to compare with, such as the Palermo Stone, the Abydos King List, or the Turin Royal Canon.

Hieroglyphs, Hieratic, Demotic, and Coptic writings

The Egyptians used four writing systems for three distinct spoken languages. The Hieroglyphs and Hieratic were used to annotate the traditional egyptian languages. Demotic was used to annotate the second phase Egyptian or Neoegyptian from the mid-end of the New Kingdom. Finally, the Coptic system was used during the Greco-Roman era to annotate the Egyptian language spoken at that time with the Greek alphabet —mind the gap— a derived alphabet from which centuries ago left the land of the pyramids through the Sinai Peninsula. The autochthon scripts (Hieroglyphic, Hieratic, and Demotic) are complex consonant writings (no written vowels) using not only phonetic, but also thousands of lexical and semantic symbols. The Hieroglyphs are a pictographic system engraved principally in stone, but also in wood and ivory, for monumental, royal, and funerary usages. While Hieratic and Demotic are cursive scripts —derived one from the other after centuries of evolution— to quickly write hieroglyphs in ink, on papyrus or ostracon, for literature and administrative purposes.

Therefore, despite being a long-lasting empire and consequently many of the archeological assets were not only deteriorated but also robbed and destroyed — not rarely by coetaneous individuals — a great part of the history of the Ancient Egypt has arrived to us by means of its written word. Hence, for any egyptologist the study of the hieroglyphic writing and derived scripts is essential. Furthermore, not few linguistics take interest in the writing systems of the Nile’s Valley in account of the unique opportunity to study a language evolution over 5000 years of use.

The Book of the Death

The life in the Ancient Egypt was profoundly affected by its funerary culture, rituals and beliefs. Guided by such devotion, they constructed colossal monuments and wonderful crafted artworks. The Book of Coming Forth by Day —commonly known as Book of the Death— is a compendium of funerary texts consisting on a series of magic spells to accompany the deceased into the afterlife. Generally written on papyrus, these documents were conveniently placed in the coffin or burial chamber. This “book” was used from the beginning of the New Kingdom and developed from the oldest Pyramid Texts and Coffin Texts. The finest example we have of it is the Papyrus of Ani. Another artifact, found by thousands along the Nile Valley, are the Ushabti, funerary figurines used throughout all of Ancient Egypt history to represent servants for the deceased to do harvest and manual labor in the afterlife.

A closing note on the origins of writing

Together with the Ancient Egypt, the invention of writing took place far apart at the same time in three more places, namely Mesopotamia, China, and Mesoamerica. However, they had apparently different purposes. The earliest written texts from Mesopotamia (site of Uruk) were accountability records such as workforce counting or tax collection. In Egypt, the earliest texts were about ceremonies, in China about divination rituals, and the Mesoamerican hieroglyphs were inspired by religious beliefs.

However, the four of them had to have a common starting point, an ignition spark which catalyzed the change, from figurative drawings like rupestrian art (Paleolithic) and then petrogliphs (Neolithic approx.) to ideograms, and later become pictograms. Evidence of intermediate stages are known as proto-writing, the tokens used to register different operations around 8000 BC in Middle East, or the Naqada glyphs in the 3rd millennium BC. This NativLang’s didactic video and G.Von Petzinger’s TED Talk explain in few minutes a millennia-long evolution process —both worth watching.

Regardless of evidences, the real understanding of why writing systems emerged could be in fact explained by the great advances they really brought, as beautifully described by the opening quote in this article.

Bonus track: the art of composing like scripting

Pepe Gimeno is a prestigious graphic and typography designer whose work is so intimately tied to the reuse of natural and artificial waste, hazardously found, but carefully balanced in his compositions. In his work, there is the recurrent idea of creating script-like compositions of beautiful harmony.

One important inference from all this is that it becomes evident that there must be some latent features shared between most, if not all, existing writing systems, which might be connected with readability by means of not only depicting salient and distinguishable shapes, but also indicating clear paths to be able to read one symbol after the other.

I hope you enjoyed this particular story of the history of writing, an amazing and exciting legacy of the Ancient Worlds.

Thanks for reading!